Priorities 1a and 1b for treasurers managing corporate cash are safety and liquidity. While yield is a close second, the returns generated on funds are generally thought of as a value add. In evaluating where to allocate cash, treasurers must carefully weigh risks versus rewards, with Money Market Funds (MMFs) and U.S. Treasury bills (T-bills) being two of the most popular vehicles for a healthy balance. Given volatility is inevitable, ensuring safety across all economic environments is essential. Here’s a breakdown of the characteristics of both options and the risks involved in times of market stress.

What Are Money Market Funds and Treasury Bills?

Money Market Funds (MMFs) Defined

Money Market Funds are mutual funds that invest in short-term debt instruments. Typically, that involves commercial paper, certificates of deposit, and government securities, but the complete list of securities that can be found in Money Market Funds is much longer, including investment-grade corporate bonds, eurodollar deposits at foreign banks, and agency securities, among others. Money Market Funds can fall into several categories based on their holdings.

Treasury Bills (T-Bills) Defined

Treasury bills are short-term government securities issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury to finance government operations. Unlike Money Market Funds, which hold a diversified mix of short-term debt instruments, T-bills are backed solely by the U.S. government, making them one of the safest and most liquid investments available. They are sold at a discount and mature at face value, meaning investors earn a return based on the difference between the purchase price and the amount received at maturity. T-bills come in various maturities, typically ranging from a few days to one year, and are widely used by institutional investors, corporate treasurers, and individuals seeking a low-risk place to park excess cash.

Money Market Funds vs. Holding T-Bills Directly

When comparing Money Market Funds and directly holding Treasury bills, key differences emerge in terms of risk exposure, liquidity, ownership structure, and leverage. While MMFs offer diversification and convenience, they introduce exposure to multiple issuers, fund manager decisions, and investor redemption risks. In contrast, T-bills provide a simpler, more direct investment option, backed solely by the U.S. government, with no pooled fund dynamics or credit exposure beyond the U.S. Treasury. The following sections break down these distinctions and their implications for corporate cash management.

Risk Exposure

In contrast to the mix of assets in a Money Market Fund with carrying credit qualities, T-bills are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. Unlike MMFs, which are subject to the creditworthiness of multiple issuers and counterparties, T-bill investors face a single credit risk: the U.S. government—historically considered negligible. That’s why returns on T-bills are commonly referred to as the “risk-free” rate.

Liquidity

T-bills are among the most liquid securities in the world and are relied upon by financial institutions for overnight liquidity. While times of stress lead to redemptions from Money Market Funds, as illustrated above, the demand for T-bills historically increases in times of crisis because of their reliability. This was evident in March 2020, when the market turmoil triggered a flight to T-bills.

Direct Ownership vs. Pooled Investment

Holding T-bills directly means investors own the security outright, eliminating exposure to the risks associated with pooled funds. MMF shareholders own shares of the fund, not the underlying securities, which means they rely on the fund manager’s decisions and are exposed to the collective actions of other investors of the fund.

No Leverage

T-bills are free from leverage, ensuring that investors' exposure remains straightforward.

With direct ownership, no exposure to pooled fund dynamics, and the backing of the U.S. government, T-bills provide a level of security unmatched by other short-term instruments. The following sections will explore how MMFs compare, examining their liquidity structure, risk factors, and the potential trade-offs treasurers should consider when balancing safety, flexibility, and returns.

Money Market Fund Risks by Type

Treasury Funds

Invest primarily in U.S. Treasury securities and repurchase agreements (repos) collateralized by Treasuries. These funds typically carry the lowest credit risk since they are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.

Government Funds

Invest in U.S. government securities, including those issued by federal agencies, and repos. These funds may hold agency securities, which, unlike Treasuries, are not directly backed by the U.S. government. This introduces a slightly higher credit risk than Treasury Funds.

Prime Funds

Invest in a broader range of short-term debt instruments, including corporate commercial paper, certificates of deposit, and asset-backed securities. Compared to Government and Treasury Funds, they carry the highest credit and liquidity risk among MMFs, as their holdings depend on the financial health of corporate issuers. During periods of market volatility, Prime Funds are more susceptible to investor redemptions and credit events, which can impact liquidity and returns.

Each fund type carries varying levels of risk, a while Treasurers investing in MMFs hold shares of the fund rather than the underlying assets themselves, they are still exposed to the risks. For example, prime funds, due to their exposure to corporate debt, may present higher credit risk compared to government or treasury funds. It's also important to note that even treasury and government funds engage in repurchase agreements (repos).

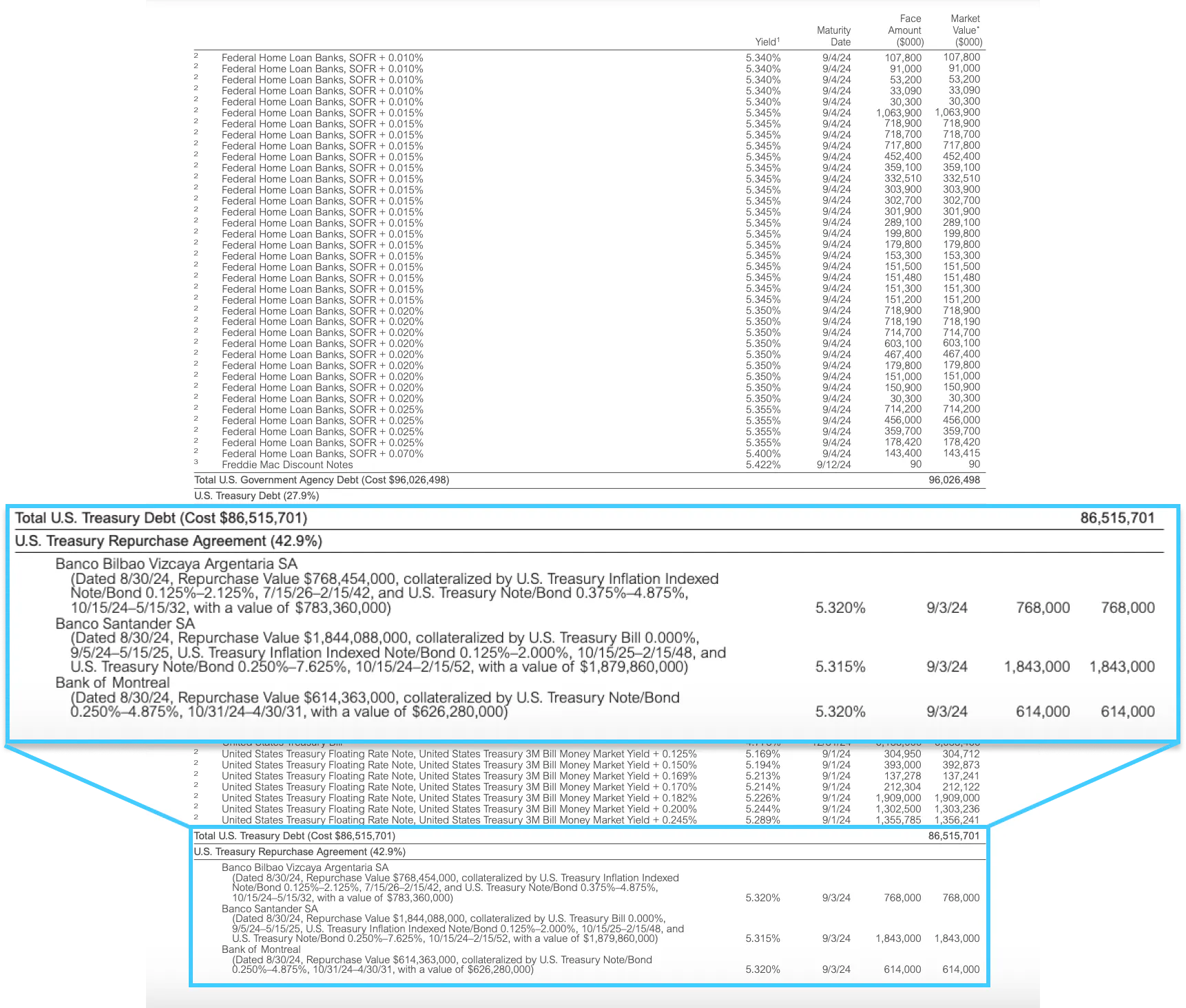

Screenshot of an example Federal Money Market Fund Financial Statement (Reporting period September 1, 2023 to August 31, 2024), illustrating the use of repos in a Money Market Fund.

Money Market Funds and Repurchase Agreements (Repos)

A repo is a form of short-term borrowing for dealers in government securities. In a typical repo transaction, one party sells a security to another with an agreement to repurchase it at a later date for a predetermined price. While repos are fairly simple and done in high volumes daily, they are not without potential pitfalls.

In many cases, there's no actual change in ownership of the collateral; instead, the collateral is segregated within the broker-dealer's (BD) accounts. In the event of the broker dealer's bankruptcy, repo agreements may not hold up in proceedings, potentially exposing investors to losses if the collateral cannot be reclaimed.

In addition to bilateral repos, many MMFs utilize triparty repo agreements, which introduces third-party clearing bank that acts as an intermediary between the borrower and lender. The clearing bank is responsible for allocating and managing collateral and facilitating daily settlement.

Every morning, triparty repo collateral is temporarily returned to the borrower so they can access liquidity, with the expectation that new repos will be initiated by the afternoon. However, during market stress, lenders may refuse to roll over repos, forcing the borrower to sell assets to meet obligations. This can lead to forced liquidations of collateral at suboptimal prices, affecting MMFs holding repo agreements.

Additionally, while triparty clearing banks manage collateral, they do not guarantee counterparty performance. If a borrower defaults and the collateral rapidly loses value, MMFs could still be exposed to losses, despite the perceived safety of the arrangement.

Money Market Funds and Risk of “Breaking the Buck”

To maintain stability, MMFs aim to keep their net asset value (NAV) at $1 per share. However, during times of significant market stress, the NAV can fall below this threshold, an event known as "breaking the buck." The last time this occurred was in September of 2008 when the Reserve Primary Fund’s NAV dropped to $0.97. The Fund had held around $785 million in Lehman Brothers' commercial paper, accounting for about 1.2% of its total assets, so when Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, it caused the Fund’s NAV to drop below $1. Worried shareholders quickly withdraw, exacerbating the problem. Eventually, it was unable to meet redemption requests, and the Reserve Fund froze redemptions for several days.

In response to such crises, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) decided to introduce reforms allowing Money Market Funds to impose "redemption gates." These gates permitted funds to temporarily suspend redemptions if their weekly liquid assets fell below a certain threshold, aiming to prevent mass withdrawals and stabilize the fund. It was a solution that helped prevent “breaking the buck,” but didn’t solve liquidity issues for end investors, it made them more likely. In 2023, SEC reforms rolled back the ability to impose redemption gates as market conditions in 2020 showed that redemption gates could have unintended consequences.

A fund doesn’t have to “break the buck” for treasurers invested in MMFs to feel the impact of a high-volume redemption. Significant redemptions may force a fund to sell its most liquid assets to meet withdrawal demands, leaving remaining shareholders with a portfolio of longer-duration, less liquid assets. In that scenario, redeeming shares for the remaining investors could potentially lead to significant performance slips, if not losses.

Conclusion: Money Market Funds & T-Bills for Treasury Cash Management

As seen in past crises, rapid redemptions and reliance on repurchase agreements can amplify stress within MMFs. This is why critical for treasurers to properly assess their exposure to potential liquidity constraints and redemption risks brought on by the underlying assets in a fund, and explore more direct, secure alternatives. Increasingly, corporate cash managers are turning to direct T-bill ownership as a way to maintain control, reduce counterparty risk, and ensure access to liquidity—especially in unpredictable market conditions.